Articles / Working with ASGI and HTTP

Our previous article introduced the ASGI protocol, and covered why having a standardized low-level server/application interface is useful, and some of the motivations for the Python community to move beyond the existing WSGI servers and start adopting ASGI.

In this article we”re going to start taking a look at the building blocks of ASGI, and demonstrate how we can start using them to write web services.

As an application developer you won”t typically be working with ASGI at the low-level, since the framework generally present a higher level interface to work with.

The ASGI callable

ASGI is structured as a pair of callable interfaces.

The first API call is a regular function call, which is made to set up a new stateful context.

The second API call is an async call, which presents a pair of communication

channels over which the server and client message each other.

Here’s how the basic structure looks:

def asgi_application(scope):

# Perform any initial state setup.

...

async def asgi_instance(receive, send):

# This is where the application performs any actual network I/O.

...

return asgi_instance

Let’s go over the arguments to those interfaces:

Scope

A dictionary of information that is used to setup the state of the application.

ASGI can be used for various interfaces, not just HTTP, so the most important

key in this dictionary is the "type" key, which is used to determine what

kind of messaging interface is being setup.

Here’s an example of the scope for a simple HTTP GET request to “https://www.example.org/”…

{

"type": "http",

"method": "GET",

"scheme": "https",

"server": ("www.example.org", 80),

"path": "/",

"headers": []

}

Send

An async function that takes a single message parameter and returns None.

In the case of HTTP this messaging channel is used to send the HTTP response.

There are two types of HTTP response message: One to initiate sending the response, and another to send the response body.

await send({

"type": "http.response.start",

"status": 200,

"headers": [

[b"content-type", b"text/plain"],

],

})

await send({

"type": "http.response.body",

"body": b"Hello, world!",

})

Receive

An async function with no parameters that returns a single message. In the case of HTTP this messaging channel is used to consume the HTTP request body.

# Consume the entire HTTP request body into `body`.

body = b''

more_body = True

while more_body:

message = await receive()

assert message["type"] == "http.request.body"

body += message.get("body", b"")

more_body = message.get("more_body", False)

Our first “Hello, World!” application

Let’s put all that together into our first simple ASGI application:

example.py

def app(scope):

assert scope["type"] == "http" # Ignore anything other than HTTP

async def asgi(receive, send):

await send({

"type": "http.response.start",

"status": 200,

"headers": [

[b"content-type", b"text/plain"],

],

})

await send({

"type": "http.response.body",

"body": b"Hello, World!",

})

return asgi

You can now run the application using any ASGI server, including daphne,

uvicorn, or hypercorn.

$ pip3 install uvicorn

[...]

$ uvicorn example:app

INFO: Started server process [30074]

INFO: Waiting for application startup.

INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

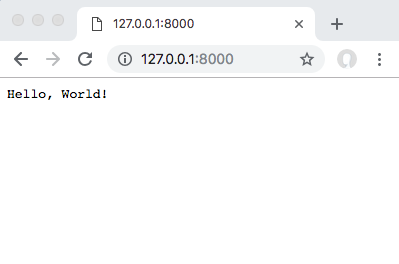

Now open “http://127.0.0.1:8000/” in your web browser:

Not super exciting just yet, perhaps? Still, it’s the basis for a whole set of functionality that isn’t possible with Python’s existing WSGI interface.

Different ways to structure ASGI applications

There are various different ways you can structure an ASGI application:

1. Using a closure to bind the scope to an ASGI instance…

def app(scope):

assert scope["type"] == "http"

async def asgi(receive, send):

...

return asgi

2. Using functools.partial to bind the scope to an ASGI instance…

import functools

async def asgi_instance(receive, send, scope):

...

def asgi_application(scope):

assert scope["type"] == "http"

return functools.partial(asgi_instance, scope=scope)

3. Using a class-based interface to bind the scope to an ASGI instance…

class ASGIApplication:

def __init__(self, scope):

assert scope["type"] == "http"

self.scope = scope

async def __call__(self, receive, send):

...

The class based interface will tend to be quite common in ASGI implementations, since it instantiates a single object on which state can be manipulated over the lifetime of a single request/response cycle.

Working at a higher level

Although it’s important to understand the fundamentals of how ASGI works, you don’t want to be working at the low level interface most of the time.

The Starlette library provides request and response classes that you can use to handle the low-level details of reading an incoming HTTP request and sending an outgoing response.

HTTP Requests

The Request class takes an ASGI scope, and optionally also the receive channel,

and presents a higher level interface onto the request.

from starlette.requests import Request

class ASGIApplication:

def __init__(self, scope):

assert scope["type"] == "http"

self.scope = scope

async def __call__(self, receive, send):

request = Request(scope=self.scope, receive=receive)

...

The request class makes the following interfaces available:

request.method- The HTTP method.request.url- A string-like interface that also gives you access to the parsed components of the URL. egrequest.url.path.request.query_params- A multi-dict, containing the parsed URL query parameters.request.headers- A case-insensitive multi-dict, containing the HTTP headers.request.cookies- A dictionary of string values, representing all the cookie data included in the request.async request.body()- An asynchronous method for returning the request body as bytes.async request.form()- An asynchronous method for returning the request body parsed as HTML form data.async request.json()- An asynchronous method for returning the request body parsed as JSON data.async request.stream()- An asynchronous iterator for consuming the request stream chunk-by-chunk without reading everything into memory.

HTTP Responses

Starlette includes various Response classes which deal with sending back the

outgoing HTTP response.

Here’s an example of using both requests and responses together:

from starlette.requests import Request

from starlette.responses import JSONResponse

class ASGIApplication:

def __init__(self, scope):

assert scope["type"] == "http"

async def __call__(self, receive, send):

request = Request(scope=self.scope, receive=receive)

response = JSONResponse({

"method": request.method,

"path": request.path,

"query_params": dict(request.query_params),

})

await response(receive, send)

The response instances present the same interface as any other ASGI instance.

To actually send the response you call it in the same way:

await response(receive, send)

That’s a nice property because it means we can use a response instance as if it was the second half of an ASGI app.

In the example above we’re not actually using any asynchronous network I/O or reading the request body, so we can simplify things a bit.

Let’s just use a plain function-based ASGI application here:

example.py

from starlette.requests import Request

from starlette.responses import JSONResponse

def app(scope):

assert scope['type'] == 'http'

request = Request(scope=scope)

return JSONResponse({

"method": request.method,

"path": request.path,

"query_params": dict(request.query_params),

})

And running our application:

$ uvicorn example:app

INFO: Started server process [30074]

INFO: Waiting for application startup.

INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

Summing up

We’ve gotten to grips with our first ASGI “Hello, World” application.

Although it’s important to understand the fundamentals of ASGI messaging, this isn’t the layer at which we’ll typically be spending out development time, so we’ve also seen how we can start to abstract those details into higher level request/response interfaces.

We’ve covered the following terms, which we’ll need whenever we’re talking about the mechanics of working with ASGI:

- ASGI Application - A callable that fulfils the ASGI interface.

- ASGI Instance - An instantiated ASGI application.

- Scope - A dictionary of information that is used to instantiate an ASGI application.

- Receive, Send - A pair of channels over which the server/application messaging occurs.

- Message - A dictionary of information, sent over either the receive or send channel.

We’re also starting to use the Starlette package, which gives us the fundamental set of tools that we need to work with ASGI at a higher level of interface.

In the next article in the series we’ll be exploring ASGI HTTP messaging in more detail.

Follow all our articles on the RSS feed.