Articles / Hello, ASGI

This article offers an introduction to the emerging ASGI standard, and what benefits it provides to Python web frameworks.

One of the newest changes in the current Python landscape is a focus on asynchronous programming models, with the introduction of async/await syntax into the language.

The asynchronous model uses lightweight task-based switching, with explicit switch points and flow control managed within the runtime. This is in contrast to thread-based concurrency, which is more resource intensive, and relies on implicit switching, managed by the operating system.

More modern runtimes such as Go and Node are based on asynchronous models. As a relatively old language, Python is having to adapt to it incrementally, which presents both opportunities and challenges.

One of these challenges is in how Python web frameworks can adapt to the potential benefits of an asynchronous model. We’ve seen this with a recent influx of high performing Python web frameworks.

A review of WSGI

The long-standing web frameworks of the Python landscape, including Django, Flask, Falcon, Pyramid, and Bottle are all WSGI-based frameworks.

WSGI is a standard that provides a formalized interface between the Server implementation, that deals with the nitty-gritty details of the raw socket handling, and the Application implementation.

Having a formalized interface here is hugely important, as it provides a proper separation of concerns between these two aspects, and allows server implementations to evolve independently of framework or application implementations.

Python has a number of WSGI servers, including Gunicorn, uWSGI, Apache/mod_wsgi, and Waitress.

I’m not going to delve into the specifics of the WSGI interface in this article, but we’ll can take a quick look at running a basic “Hello, world” web service:

example.py:

def hello_world(environ, start_response):

data = b"Hello, World!\n"

start_response("200 OK", [

("Content-Type", "text/plain"),

])

return [data]

We can now run our hello world application with any WSGI server:

$ gunicorn example:hello_world

WSGI has been hugely successful, and it’s near-universal adoption is testament to the importance of a server/application interface, but it comes with a couple of constraints that are not easily overcome without a significant overhaul.

For one thing, WSGI is necessarily a thread-based or greenlet based interface, and cannot support an async/await model. WSGI is inherently not able to take advantage of the potential benefits of asynchronous programming.

For another thing, WSGI is strictly an HTTP interface, and cannot easily be adapted to provide support for WebSockets or other network protocols.

Enter ASGI

This is where ASGI comes in.

The ASGI specification is an iterative but fundamental redesign, that provides an async server/application interface, with support for HTTP, HTTP/2, and WebSockets.

For contrast, here’s an example of an ASGI “Hello, World” service.

example.py:

class HelloWorld:

def __init__(self, scope):

pass

async def __call__(self, receive, send):

await send({

'type': 'http.response.start',

'status': 200,

'headers': [

[b'content-type', b'text/plain'],

]

})

await send({

'type': 'http.response.body',

'body': b'Hello, world!',

})

We can run our example by installing an ASGI server. In this case, using uvicorn:

$ uvicorn example:HelloWorld

Again, I won’t go into the specifics of the specification in this article, but two key things to note in the interface are:

- The

asyncsyntax in the__call__method, which explicitly marks it as a possible point of task-switches, and allows other asynchronous code to be used within that execution context. - The

receiveandsendparameters, over which the messaging between the server and application takes place.

This async/await based interface has a number of advantages over WSGI.

Performance characteristics

Async code is able to attain significantly higher throughput than thread-based concurrency in cases where code is primarily network-bound, rather than compute-bound. The resource efficient switching of task-based concurrency means that thousands of lightweight tasks can be executed alongside each other, without the high overhead of thread-based switching. This means that each single server or instance is able to support a far larger volume of traffic.

Python frameworks have historically been a poor candidate for certain classes of use-case where asynchronous runtimes such as Node or Go have excelled.

The ASGI specification provides an opportunity for Python to hit a productivity/performance sweet-spot for a wide range of use-cases, from writing high-volume proxy servers through to bringing large-scale web applications to market at speed.

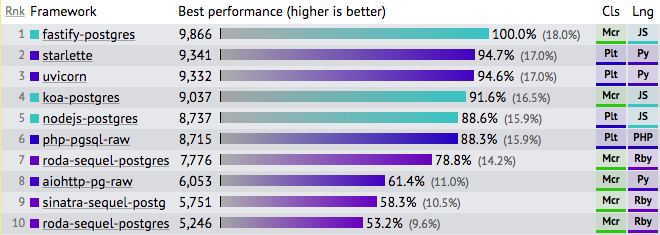

For example, here’s the latest suite of results from the TechEmpower benchmarks, filtered down to a few dynamic languages (Python, JavaScript, Ruby, PHP, Perl) all using a Postgres backend:

With Starlette and Uvicorn towards the top of the list, Python comes out of those benchmarks with comparable performance characteristics to Node.

Support for WebSockets and long-lived HTTP connections

ASGI directly supports WebSockets, allowing developers to build more responsive web applications, and other highly interactive services that are not well suited to HTTP.

It can also used to support HTTP long-polling, or HTTP Server Sent Events, which allows for uni-directional server-to-client updates.

Support for HTTP/2

ASGI is able to support HTTP/2 server-push, allowing frameworks to preemptively send additional media to the client when a page load is performed. This be can used to achieve lower latencies for websites that are able to avoid some of the required roundtrips that characterize the loading of a webpage over HTTP/1.1.

In-process background tasks

The messaging model that ASGI provides means that it is able to continue to run code after the HTTP response has been sent. This allows frameworks to provide lightweight in-process background tasks, without the need for infrastructure to support a full-blown task queue.

Extensibility

Where WSGI presents an interface of “call into this function with an HTTP request, and wait until an HTTP response is returned”, the ASGI specification presents a more broadly extensible interface of “here’s a pair of channels between which the server and application can communicate”.

This more general pattern has the potential to be extended into other protocols beyond HTTP or WebSockets.

Where are we now?

There are a number of production-ready ASGI servers:

daphne- The original ASGI server. Originally developed for Django channels.uvicorn- A high performance ASGI server, with an implementation based on uvloop and httptools.hypercorn- A fully-featured ASGI server, including support for features such as HTTP/2 server push.

Each of these has a measure of established production-use, and all three have helped inform the refinement of the ASGI specification.

There are also a few different ASGI frameworks.

channels- Django’s answer to WebSocket support. Provides a thread-based application context over an async-based server implementation.starlette- Starlette is designed to be used either as a fully featured Web framework, or a toolkit for working with ASGI. A high performance framework with a feature-set that is similar in scope to Sanic or Werkzeug.quart- A Python ASGI web micro-framework with the same API as Flask.

ASGI also provides a manageable upgrade path for existing web frameworks to provide async support, since it maps well onto WSGI while adding additional capabilities.

There are positive noises from the maintainers of Werkzeug/Flask, and from the Falcon team. There’s also been consideration from the Django team about bringing ASGI support into the core framework.

There is also tentative support from maintainers of some asyncio-based frameworks, including Sanic.

Continuing this series

My development work here is focused on the ASGI server, Uvicorn, and the ASGI framework, Starlette.

Over the coming weeks I’ll be writing in more detail about working with ASGI, including how to use it to build WebSocket-based applications, HTTP proxy servers, ASGI middleware, and more.

Our next article will start looking in more detail at working with HTTP in ASGI.

Follow all our articles on the RSS feed.